Adam Lovell wants you to become pen pals with one of the 2.3 million Americans serving time in jail or prison.

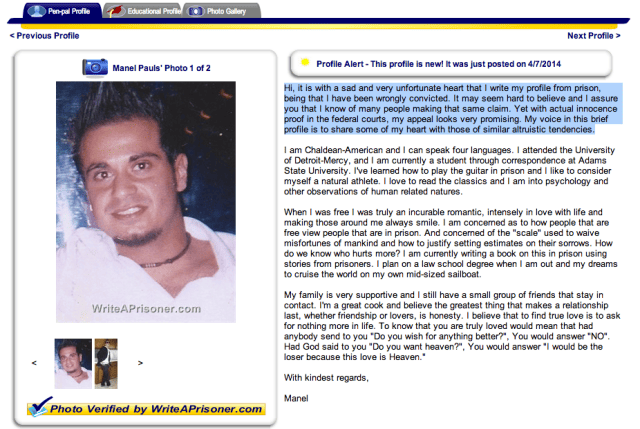

Lovell is the founder of WriteAPrisoner.com, a website that lists personal ads from prisoners seeking pen pals. A visitor to the site might decide to become pen pals with Jacoby Bright, a 22-year-old New Orleans native incarcerated for illegal possession of stolen items, attempted manslaughter, and attempted robbery. He asks potential pen pals to “Become my angel, the most precious thing in my life aside from my son.” Another visitor may debate whether to believe inmate Manel Paul, who writes that he has “been wrongly convicted” of armed robbery and that his appeal looks promising. Paul also acknowledges that many prisoners claim innocence and says that he wants “to share some of [his] heart with those of similar altruistic tendencies.”

WriteAPrisoner is not the only site in the prison pen pal business. The public can also find an inmate to correspond with through PrisonPenPals, Inmate.com, Friends Beyond the Wall, and Meet an Inmate.

Inmates pay $40 to list their profile on WriteAPrisoner for a year. Renewing the profile for another year costs an additional $30. As prisoners don’t have Internet access, WriteAPrisoner sends brochures to prisons that inmates can use to create a profile by mail. The company has since made it possible for inmates’ friends or family to create a profile and pay the fee on their behalf on WriteAPrisoner.com. Lovell and his small staff vet each new profile by running a background check. Inmates’ profiles include their prison address so that members of the public can mail them directly. WriteAPrisoner also offers to facilitate pen pals’ first correspondence by printing out an email and sending it to the prisoner.

If you don’t see the appeal of swapping letters with an inmate, you’re not alone. But plenty of Americans do. According to estimates from Quantcast, WriteAPrisoner gets about 4,000 to 6,000 unique daily visitors to its site. Around 150,000 people have sent a prisoner a letter through the website, plus an unknown number who contacted a prisoner through postal mail and all those pen pals who used another prisoner correspondence site.

A Link to the World

“Prison has taught me the true meaning of loneliness – what it means to be separated from everything that’s real… My struggle is [to not] become a product of this environment.” ~WriteAPrisoner user from Malone, Florida

It’s hard to imagine the criminals from America’s favorite gangster movies spending their prison stints exchanging letters with an anonymous office worker or quiet retiree. But outside of Hollywood, many prisoners are eager for contact and human connection, whatever its source.

“In prison you can’t show weakness, you’re not allowed to be human,” Adam Lovell told us over the phone from his home in Florida. Lovell has corresponded with friends who went to prison, and he has read thousands of the initial letters that people email to WriteAPrisoner. Lovell describes the pen pal program as an opportunity for prisoners to express vulnerability, hear news from outside prison, and be themselves. “Prisoners can be a bit delusional about who will stick with them” through their sentence, he says. When contact from friends and family drops off, “a senior citizen at other end of world is better than nothing.”

Lovell clearly believes that prison correspondence has a positive impact. He was inspired by the example of his mother, who tutored illiterate prisoners at the request of a Pennsylvania prison when no one else volunteered, as well as by ministries who have long helped inmates find pen pals. “I think they’re doing a good thing,” he told us.

In 2000, Lovell started WriteAPrisoner, figuring that charging a fee to fund a website would grow the practice. He worked as a lifeguard, expecting to run the website as a passion project in his spare time. But in 2003, he “quit the beach” to work on the company full-time. Between fees and revenue from a small number of ads on the website, Lovell can now employ four 40-hour a week employees.

Lovell peppers a page on the site titled “Why WriteAPrisoner” with quotes and citations about the importance of connections for prisoners’ social adjustment and emotional well-being, especially after their release in deterring recidivism. He also notes that many pen pals have helped inmates find housing or employment after their release, which can be a huge challenge and often a condition of parole. WriteAPrisoner has employment, scholarship, and “Books Behind Bars” sections. Contractors are working on a redesign of the site (“We’ve been operating in dark ages,” Lovell says) that will feature those programs more prominently, introduce a Share a Ride program to help pen pals visit inmates in remote jails, and implement features borrowed from social media like logins, a following feature, and notifications.

Pen pals can offer prisoners “a better outlook on life and gives them a connection to something positive,” says Lovell. “It’s a social connection to a world they will one day be released to.”

Source: WriteAPrisoner. First paragraph highlighted by the author.

The Demographics of Prisoner Pen Pals

So who becomes pen pals with America’s prisoners? Lovell says they come from all walks of life, but he cites a few main groups.

The “largest minority” of pen pals correspond for “faith based reasons.” Like the faithful that ministries would connect to prisoners, members of each religion seek out pen pals from the same faith.

Other writers include soldiers stationed overseas who appreciate swapping letters because they have limited connectivity themselves as a condition of their service — something Lovell concedes he never expected. A number of law students become pen pals as well, often encouraged by their law professors.

The rest come from every demographic. “I don’t know the rhyme or reason for why most people write,” Lovell says. He thinks there is a fascination with the unknown aspect, the type of interest that makes a show like NBC’s documentary Lockup popular.

Lovell supports the flow of information about prison life to the general public. Lovell writes on the site that his great uncle died in prison, allegedly of suicide, but an autopsy showed he was beaten to death: “A letter smuggled out from an inmate to my great-grandmother claimed the guards did it and then dragged his body by their cells as a warning to other inmates.” For those not up for finding a pen pal, a program on Quora allows prisoners from San Quentin prison to answer questions from the public about prison life.

Foreigners write as well, something Lovell ascribes to the empathy of foreigners who see American prisons as “harsh” and “austere.” For these pen pals, America’s prisoners need the extra support. “In Norway’s prisons, you can ski,” Lovell offers.

Some prisoners and members of the public also treat sites like WriteAPrisoner as a dating website. A New York Times article in 2000 about an earlier prison pen pal site described a psychotherapist named Diane who fell in love and planned a wedding with an inmate all before her pen pal turned fiancé was released from prison.

“I think a lot of people are hopeful that they’ll find love on the site,” Lovell says in answer to the dating question. “We have a lot of stories of people who become romantically involved, but it’s small in the scope of how many people we have.” A few sites that he dislikes, like Women Behind Bars, play up the fantasy aspect of a relationship with an inmate. But his staff bans racy photos and discourages dating profiles, telling inmates that they’re less likely to receive mail if they look for love. People pay attention to the romance aspect, but “it’s really about outside contact at the end of the day.”

The Pen Pal Biz and Its Critics

In 2005, conservative pundit Bill O’Reilly got wind of the prison correspondence niche. He was not a fan. Assuming that the prisoners used email since the ads were on websites, Lovell says, he denounced giving prisoners Internet access.

O’Reilly also hosted Cindy and Mark Sconce, who expressed outrage that the man imprisoned for raping and murdering their daughter could describe himself in his profile as “honest, outgoing, loving, and caring.” Cindy Sconce told O’Reilly:

“Everybody says this is his right to freedom of speech. But in my mind, because he was convicted of kidnapping and raping and murdering our daughter, he should have no rights. He should have the same rights [our daughter] Courtney has right now.”

In 1999, the Times quoted a Republican member of the House who pushed for such sites to be banned, describing how a man who murdered his fourth wife was advertising that he enjoyed “long walks in the moonlight.” A democratic state assemblyman described a constituent who, like the Sconces, called himself traumatized by finding a profile created by his daughter’s killer.

Commentators on Prison Talk, a “prison information and family support community,” responded to O’Reilly’s segment by asking how parents could come across the profiles if not seeking them out. Several also criticized O’Reilly’s seeming belief that prisoners should be shorn of all rights and any ray of light. “O’Reilly is the type of guy who feels anyone convicted of any crime should be kept in a concrete cell 23 hours of the day… I’ve never understood the idea of a victim being victimized again because said criminal gets visits from loved ones or a letter from a stranger,” one user wrote.

It does seem disconcerting that pen pals give their address to criminals. WriteAPrisoner advises that people can get a PO Box, but using snail mail doesn’t allow for real anonymity or keeping locations private. Although it has not happened through WriteAPrisoner, Lovell says that he has seen stories of inmates murdering pen pals. “With the volume we do, we’re bound to see every story,” he says.

But Lovell expresses confidence in the background checks performed by WriteAPrisoner, the warnings about sending money they provide to users, and the intelligence of the pen pals. Lovell says that they’ve only received complaints about inmates seeking money under false pretenses, and that WriteAPrisoner only receives two legitimate complaints per year. “I know it sounds made up,” he says, “but it’s true.”

The merits of the prisoner correspondence business are clearest when considering the type of criminals that make up the brunt of America’s prison population. People can debate whether inmates like the killer of Cindy and Mark Sconce should be able to solicit a pen pal — on public safety grounds and on the question of whether it’s protected by freedom of speech. (New York, for example, banned sending prison mail through third parties for security reasons.) But an incredible number of prisoners who could benefit from sites like Adam Lovell’s are far from hardened criminals.

Lovell points to the statistic that America represents 5% of the global population but 25% of the world’s prisoners as a reason for why efforts to fight recidivism are so important. Half of the over 216,000 federal inmates in the U.S. are incarcerated for drug-related offenses. Approximately 70% of them would benefit from the Obama Administration’s push to reduce sentences for nonviolent drug crimes if applied retroactively.

On WriteAPrisoner, Adam Lovell describes a childhood friend who went to prison for a small offense and then killed another man over a minor argument after his release. “Before this, I ran into him at the state college, and he was trying to get his life back on track,” he writes. “My preferred memory of him is still as the boy who stashed my bike in the woods and pedaled me miles home on his handlebars when I cut my foot open on an oyster bed as we were dragging a sand net in the Indian River. We were maybe ten or eleven years old, and it is a reminder – to me, at least – that a person should not be judged on their worst deed.”

The tens to hundreds of thousands of Americans who have become pen pals with prisoners seem to have come to the same conclusion.

This post was written by Alex Mayyasi. Follow him on Twitter here or Google Plus. To get occasional notifications when we write blog posts, sign up for our email list.